How supply chain shocks have changed the face of global trade

In the autumn of 2021, rows upon rows of containers sat idle at the port of Felixstowe in Suffolk. A shortage of lorry drivers meant goods could not leave the UK’s largest container port quick enough.

The logjam raised concerns in the UK that toys, beauty products and other presents would not arrive in time for Christmas.

But the supply chain adapted. Shipping companies diverted vessels to other ports, including Wilhelmshaven in Germany. Smaller ships then carried goods from these alternatives to other ports in the UK to more evenly distribute containers across the country. Christmas was saved.

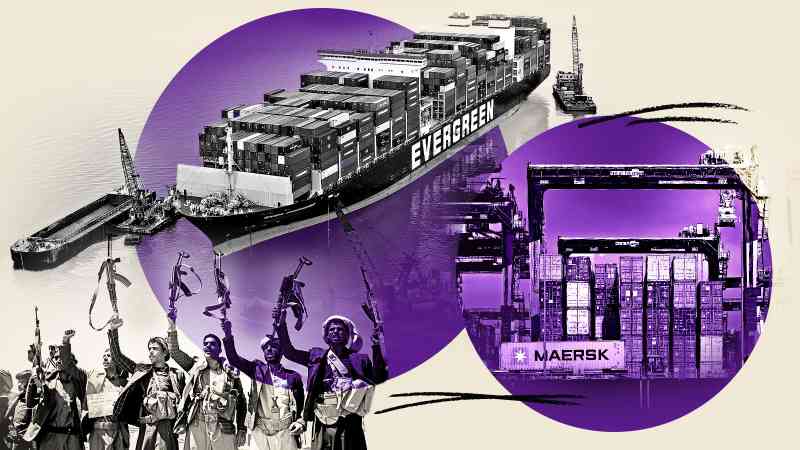

This episode, alongside the increase in goods spending during the pandemic, the Suez Canal blockage caused by the stranded Ever Given ship and recent Houthi rebel attacks in the Red Sea have thrown the interconnectedness of the global shipping network into the spotlight.

Production of tradable goods has been a global enterprise since the 1990s, underpinned by the fluidity of supply chains. About 80 per cent of internationally traded goods are carried by the container ship industry. However, the march of globalisation has slowed in recent years.

A series of shocks to the flow of global trade have made businesses more aware of the dangers involved in setting up a supply chain that is both geographically dispersed and reliant on “just in time” production.

Countries and companies are turning inward. Businesses are bringing supply chains closer to home, reducing their reliance on nations that are perceived to be political or military threats and upending stock-building patterns to ensure they have enough products during periods of intense demand

A particularly big supply chain shock came with the pandemic. Ports shut down routinely to contain virus outbreaks and the Suez Canal was blocked by the Ever Given ship in 2021, triggering a steep rise in freight costs.

Recent tensions in the Middle East have made safe passage through the Red Sea nearly impossible, forcing vessels to divert around the Cape of Good Hope in southern Africa, elongating transit times.

Industrial action has also shut ports and railways. This month, about 9,300 rail workers in Canada were shut out by the Canadian National Railway and Canadian Pacific Kansas City after negotiations with the Teamsters union broke down.

According to Project44, a research firm that monitors global shipping flows, transit times for containers travelling from China and southeast Asia to Europe and the US East Coast have increased by about ten days on average since the Houthi rebel attacks in the Red Sea started in the winter of 2023.

In response to this intensifying strain on the international shipping network, retailers are trying to get hold of stock earlier.

Peter Jameson, managing director and partner at the Boston Consulting Group, said there had been “a strategic shift towards pre-emptive stockpiling and a proactive approach that has been taken in response to lessons learnt from previous disruptions, where delays and shortages severely impacted profitability during peak seasons”.

“There is also a strategic necessity to replenish earlier. In today’s uncertain environment, businesses that do not plan ahead, by securing inventory early, risk facing stockouts. This is especially true during the critical holiday season,” he added.

This sudden burst in buying from retailers can actually cause the exact thing they are trying to avoid: shortages.

The boss of the world’s second-largest container shipping company recently warned that high orders for the festive period risked deepening delays and congestion across the global supply chain.

Vincent Clerc, the chief executive of AP Moller-Maersk, told the Financial Times: “At this stage the thing that can really make things worse for the global supply chain is this rush for the door where everybody starts to order more than they need. You get this bullwhip effect.”

Paul Hayes, chief executive of Seasalt, a clothing brand that operates in the UK and the US, said the company had ordered stock earlier than usual for Christmas “to meet customer expectations across our channels in the run-up to the season, given the situation with the Red Sea delays earlier this year and in anticipation of further unrest globally for the remainder of 2024”.

He said the British brand had “record” stock levels in its distribution centres in preparation for the peak trading period.

Political upheaval in Bangladesh, a linchpin of the global garment industry, has delayed clothing deliveries. “Our increased stock levels will also de-risk the potential impact on our business from expected disruption in the country,” Hayes added.

• Seasalt sales rise on tide of shop openings

The chief executive of a large UK fashion retailer said that shipping distribution was currently “more unpredictable” than ever.

“The [widescale] disruption has added ten days to our lead times and on top of that a growing unreliability that your stock will definitely get onto your booked vessel and, importantly, your booked route.

“If your vessel takes a different route, it can add another week. Businesses that operate close to the season, ie fast fashion, will no doubt be feeling the impact.”

Two of the world’s busiest waterways — the Panama and Suez canals — have undergone severe disruption in the past few years.

The Panama Canal has suffered from historically low water levels due to drought, illustrating the dangers that climate change will pose to the functioning of the international shipping system. The Suez was gummed up by the marooned Ever Given ship in 2021 and is now underutilised thanks to Houthi attacks.

These disruptions illustrate the risks of overreliance on a limited number of waterways.

Jenna Slagle, senior data analyst at Project44, said: “What is key to remember is that while these canals offer major time savers, even without them, carriers can adjust and continue to deliver goods.

“The biggest change will be transit time, and while that is impactful, with the improved technologies among supply chains, companies can adjust ordering logic to either rely more heavily on West Coast ports or account for the additional transit time.”

Protectionist trade policy has been more frequently employed in recent years, with China often the victim. The United States recently slapped a 100 per cent tariff on Chinese electric vehicles. The European Union is following a similar path, though less punitive. Beijing has retaliated.

Although relinquishing his lead in the US presidential election polls to Kamala Harris, the Democrat nominee, Donald Trump has insisted he will instil further protectionism into the US’s trade strategy. At a recent rally, Trump advocated for “10 to 20 per cent tariffs on foreign countries that have been ripping us off for years”.

• Biden’s tariffs against China are about more than economics

Trade barriers can protect industries and workers at risk of competition from overseas and smooth the early development phase for nascent sectors at the technological frontier. However, they can also weaken demand by raising goods prices, leading to less trade overall. Shippers can adapt to higher taxes by stepping up activity in countries where tariffs are lower.

Simon Heaney, senior manager of container research at Drewry, a maritime research firm, said: “The lesson from the earlier Trump tariffs in 2018 was that container trade finds the path of least resistance.”

“They didn’t so much curb trade in containerised goods but redirected it where barriers were lower [such as Vietnam].”

Strain on supply chains has not reached levels seen during the pandemic when lockdowns ignited a surge in spending on goods. Freight rates are still well below the peaks reached in 2021.

However, the experience of several bouts of disruption in a short period has reconfigured businesses’ preferences and behaviour.

Nearshoring, greater scepticism of the just-in-time delivery model and the return of isolationist trade policy could markedly change the complexion of the international shipping network in the years to come.